C L A Y _ H A M M E R _ 2017 _ М О Л О Т О К _ І З _ Г Л И Н И

Natalia Laluq artist statement 3, in quotes, for the Clay Hammer series:

“ ‘ That was the clay machine-gun/ said Chapaev… ‘That’s it/ said Chapaev. ‘That world no longer exists.

‘Damn,’ I said, the papyrosas were still in there…’”

-Victor Pelevin from “Buddha’s Little Finger”

“… , we can conclude that contemporary works can be evaluated critically in terms of success and failure only

if we take these terms in their most organic sense (to replace the vague dichotomy between beauty and ugliness,

poetry and non-poetry). Which in turn means that even in those cases in which the structural model of a work

appears as the primary value realized and communicated by the form (in other words, when the work appears mostly

as a vehicle for a poetics), the work fulfills its fullest aesthetics value only insofar as the formed product

adds something to the formal model (so that the work manifests itself as the “concrete formation” of a poetics).

The work is something more than its own poetics (which can be articulated also in other ways), since the very

process by which a poetic model acquires a physical form adds something to our understanding and our appreciation.”

- Umberto Eco, from “The Open Work (Two hypotheses about the death of art)”

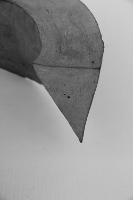

Natalia Laluq artist statement 1 for the Clay Hammer show in RKG Gallery:

I work with clay for a long time, almost as long as the clay works with me. As long as we work together we learn from each other and

sometimes we get into that relaxed collaborative mode where we can undoubtedly admit that we understand each other.

Presented is the result of such “meeting-clay-as-your-old-friend” session.

Natalia Laluq artist statement 2 for the Clay Hammer series:

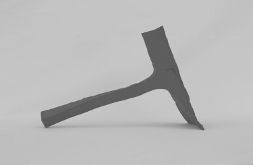

Clay Hammer

Why did I make clay hammer?

I spoke with my son this morning and he commented on my clay hammer sculpture (now on display at Robert Kananaj Gallery, 172 St. Helens Avenue,

Toronto, until the 7th of October, 2017). He associated the piece with the communist symbol. I also heard same comment from my friends, and from

visitors to the gallery.

This can be one of the readings, however, my message is not in the past, but in the present and future.

We are producing the weapons, which when used, crush themselves and crush and destroy us. When I look at this object, my first reaction is a

conflict in between how robust and bold, aggressive it wants to appear, and how fragile and weak it is in its essence. If one will try to use

it as a hammer, just only once, the hammer will be crushed. The irony of this unveiling crisis of the world – is that we try to threaten each

other by clay hammers.

Глиняний молоток

Чому я зробила глиняний молоток? Сьогодні зранку, я розмовляла зі своїм сином і він виказав свою думку щодо моєї скульптури глиняного молотка

(зараз на показі в галереї Robert Kananaj Gallery, 172 St. Helens Avenue, Toronto, до 7-го жовтня 2017). Йому видається, що ця скульптура є

аналогом символу комуністичної доби. Такі ж відгуки я чула від моїх друзів та відвідувачів виставки. Звичайно, це може бути однією з

інтерпритацій, проте ідея цієї скульптури звернена не до минулого, а радше до теперішнього та майбутнього часів.

Ми продукуємо зброю, яка у разі використання, руйнує як себе, так і людство. У цій скульптурі я спостерігаю проявлення конфлікту:

одночасне намагання обєкту бути брутальним та агресивним, коли, насправді, цегляний молоток є дуже слабким та крихким у своїй суті.

І якщо ми наважимося цей молоток із глини вжити, - бодай тільки раз, то звичайно він розібється, не дивлячись на всю, здавалось би на

перший погляд, надійність, витривалість та чіткий намір підтвердити свою силу у агресивній дії. Іронія, закладена в цій скульптурі,

викриває кризу сучасного світу, коли ми погрожуємо один одному молотками із глини.

Toronto, 2017